Untold Story of the Mighty Indus River

"How the river that once built empires is now on the brink of collapse."

A River’s Cry for Survival

It once carried the hopes of entire civilizations. Today, it carries only warnings. The Indus River, also known as Sindhu Darya, has shaped history, fed millions, and created empires. But in 2025, this mighty river is in crisis. Canals are dry. Farmers are desperate. In Sindh, a growing drought has left towns without drinking water and fields without crops. This is not just a story about a river — it’s a warning for an entire region.

Sindhu Darya: River of Life

The Indus River begins in the mountains of Tibet, flows through India and into Pakistan, and finally falls into the Arabian Sea. It travels over 3,000 kilometers and passes through Gilgit-Baltistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab, and Sindh. More than 220 million people depend on it for water, food, and electricity. Its main tributaries — Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej — join it to form the vast Indus Basin.

A River That Gave Birth to Civilizations

Thousands of years ago, the banks of the Indus were home to the Indus Valley Civilization. Cities like Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro were built near the river. People used the water for farming, trade, and daily life. Even today, remains of those cities show how organized and advanced their society was. The river was at the center of everything.

How Water Became Political

During British rule, engineers built canals and barrages to control the Indus and use its water for agriculture. After the 1947 Partition, India and Pakistan were born — and so were new water problems. India controlled the upstream rivers. Pakistan, being downstream, feared water shortages. Tensions started early, and water soon became a political issue.

The Indus Waters Treaty: A Fragile Peace

In 1960, the Indus Waters Treaty was signed with help from the World Bank. The agreement gave Pakistan control over the western rivers — Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab — and gave India the eastern rivers — Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej. The treaty has survived wars. But today, it’s under stress. India is building more dams in Jammu & Kashmir, such as the Kishanganga and Ratle projects. Pakistan says this limits water flow to its lands. Climate change and growing populations are making the treaty look outdated.

Sindh in 2025: Dry Lands and Desperate People

This year, the situation in Sindh is alarming. Water levels at Kotri, Sukkur, and Guddu barrages have dropped severely. According to the Pakistan Meteorological Department, rainfall was 45% below average this season.

In villages of Badin and Tharparkar, people walk for hours just to find water. Farmers say their wheat and cotton crops have failed. In cities, water tanker mafias sell water at high prices. The Indus Delta — once lush and green — is shrinking fast. Seawater is moving inland, destroying farmland and poisoning groundwater.

Floods Still Linger in Memory

Even though Sindh is dry now, the threat of floods is not gone. In 2010 and 2022, major floods displaced millions. These were caused by heavy monsoon rains and melting glaciers. Scientists warn that climate change is causing both droughts and floods — a dangerous cycle for a river system already under pressure.

Dams and Barrages: Control vs. Crisis

Major Dams in Pakistan

- Tarbela Dam (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa): One of the largest earth-filled dams in the world. It generates electricity and stores water.

- Mangla Dam (Azad Kashmir): Built on the Jhelum River. Helps with water supply and flood control.

- Chashma Barrage (Punjab): Regulates river flow and supports agriculture.

Sindh’s Key Barrages

Sindh depends heavily on the Indus River for agriculture and water supply. Three main barrages in the province help control the flow of water and distribute it through canals to farmlands. These are:

Guddu Barrage

- Location: Near Kashmore, northern Sindh

- Built in: 1955

- Purpose: Supplies irrigation water to over 2.9 million acres of land through canals like the Ghotki Feeder, Begari, and Desert canals

- Importance: It regulates the Indus flow coming from Punjab and distributes it into upper Sindh. Also used for flood control.

Sukkur Barrage

- Location: Sukkur city, central Sindh

- Built in: 1932 (formerly called Lloyd Barrage)

- Purpose: Oldest and largest barrage in Pakistan in terms of canal command area. Feeds seven major canals.

- Importance: Irrigates over 7 million acres of land — vital for Sindh’s agriculture, especially rice, wheat, and sugarcane.

Kotri Barrage

- Location: Near Hyderabad, southern Sindh

- Built in: 1955

- Purpose: Last barrage on the Indus before it reaches the Arabian Sea. Controls water flow to lower Sindh.

- Importance: Supplies water to the Kalri Baghar, Pinyari, and Fulleli canals. Crucial for irrigation in southern Sindh and maintaining freshwater flow to the Indus Delta.

These barrages are lifelines for Sindh's irrigation system. But with low upstream flow, they are almost dry.

New Dams Under Construction

- Diamer-Bhasha Dam: Under construction in Gilgit-Baltistan. Expected to store 8 million acre-feet of water and produce 4,500 MW electricity.

- Mohmand Dam: In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, planned to reduce flood risk and generate power.

Experts say Pakistan needs dams to store water. But environmentalists warn about displacement, ecological damage, and earthquake risks.

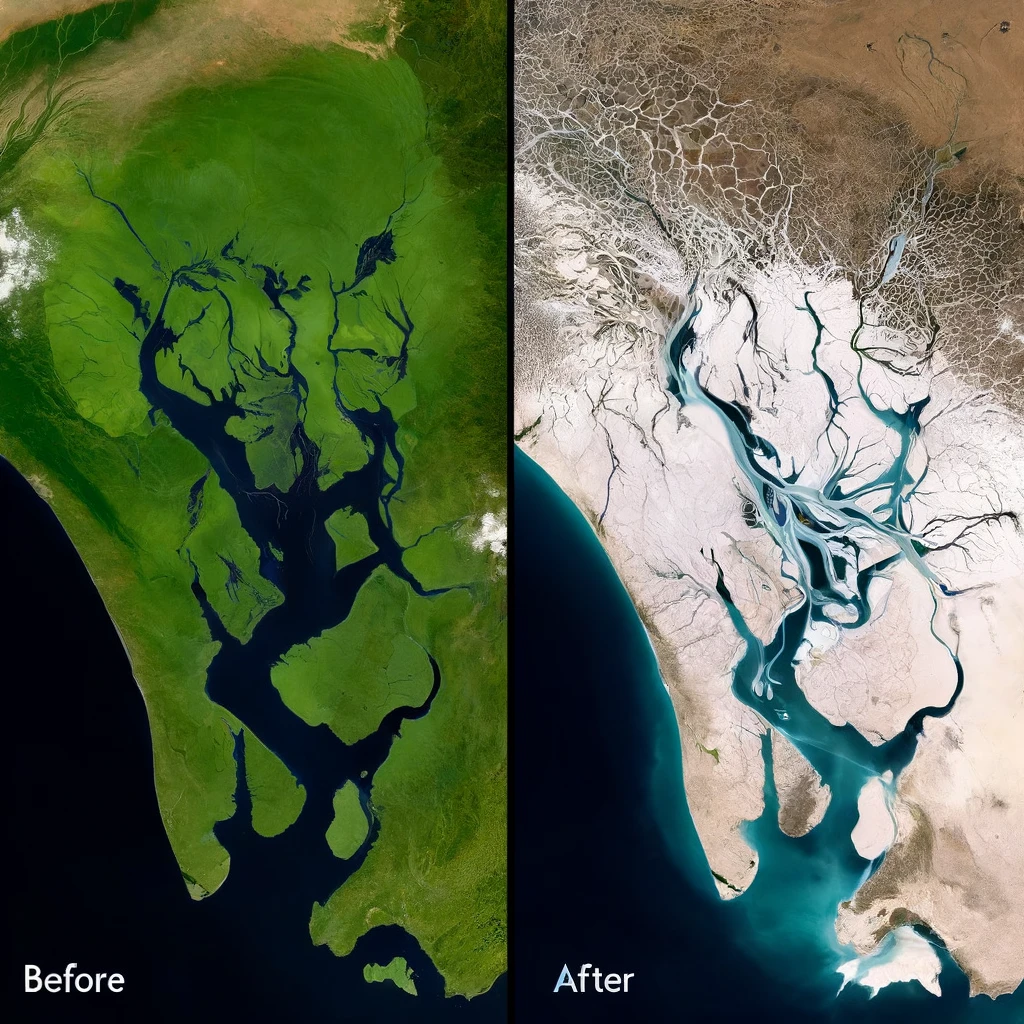

The Shrinking Indus Delta

The delta, once 600,000 hectares in size, is now less than half. Due to upstream water use, little freshwater reaches the sea. This has caused:

- Saltwater intrusion

- Mangrove forest destruction

- Loss of fisheries

- Rising poverty in coastal Sindh

Real People, Real Struggles

🗣️ “My fields are dry. My animals are dying. There’s nothing left,” says Ghulam Hussain, a farmer near Badin.

🗣️ “We used to get water from the canal. Now we walk for 2 hours to find it,” shares Rehana, a mother in Thar.

🗣️ “The sea is coming into our land,” says a boatman in Thatta. “Soon, we’ll have no home.”

These voices show the human cost of a drying river.

River of Conflict or Cooperation?

India and Pakistan share the same river, but not the same vision. There is no joint action plan for glacier melting, river health, or water emergencies. Experts say it's time for:

- Revising or modernizing the Indus Waters Treaty

- Transparent dam building practices

- Joint climate monitoring and flood alerts

- Shared ecological responsibility

What Can Be Done Now

- Protect the ecological flow of the Indus

- Modernize the water-sharing treaty

- Fund drought response programs in Sindh

- Train local farmers in climate-smart agriculture

- Invest in early warning systems for floods

Conclusion: Will the Indus Still Flow for Our Children?

The Indus River built civilizations. It gave names to nations. It connected people, cultures, and faiths. But today, it is breaking apart — dried by heat, blocked by dams, and ignored by those who depend on it most. If we want a future for Sindh, for Pakistan, and for the millions who rely on Sindhu Darya, we must act now. Because if we lose the Indus, we lose more than just water — we lose history, hope, and harmony.