Fall of Bashar Al-Assad Regime

The History of the Assad Regime and Its Potential Fall

The Assad regime has ruled Syria for more than five decades, maintaining a firm grip on power through authoritarian governance, military dominance, and strategic alliances. The regime was founded by Hafez al-Assad in 1970 and later continued by his son, Bashar al-Assad. The family's rule has been marked by internal conflicts, regional interventions, and a brutal civil war that began in 2011. While many analysts have speculated about the collapse of the Assad regime due to ongoing instability, the government remains in power with external support. This discussion will provide a detailed historical account of the regime's rise, its consolidation of power, the 2011 uprising, the subsequent civil war, and the factors that could contribute to its eventual fall.

1. The Rise of the Assad Regime (1970-2000)

Hafez al-Assad's Coup and the Establishment of a Dictatorship

Syria gained independence from French colonial rule in 1946, but the post-independence period was marked by political instability, military coups, and external interventions. By the late 1950s, the Ba'ath Party, a pan-Arab socialist movement, gained influence in Syria, promoting Arab nationalism and socialist economic policies. In 1963, the Ba'ath Party seized power in a coup, leading to a period of infighting among military officers and party factions.

Hafez al-Assad, an air force officer and Ba'athist leader, took advantage of these internal conflicts. In 1970, he led a bloodless coup (the "Corrective Movement"), overthrowing his rivals and establishing himself as the undisputed ruler of Syria. Over the next few decades, Hafez consolidated power by:

- Centralizing authority within his Alawite-dominated inner circle.

- Crushing political opposition, including communist groups, Islamists, and other factions.

- Building a strong security state through military and intelligence agencies (Mukhabarat).

Domestic and Foreign Policies Under Hafez al-Assad

Hafez al-Assad established an authoritarian one-party system that suppressed dissent and ruled through a combination of brutality and strategic alliances. He maintained strong ties with the Soviet Union during the Cold War and positioned Syria as a key player in Middle Eastern politics.

Domestically, his policies included:

- Economic centralization: The state controlled major industries, land reforms were introduced, and subsidies were provided to the lower classes.

- Repression of political opposition: The 1982 Hama Massacre became a symbol of Assad's brutality. The regime crushed an uprising by the Muslim Brotherhood in Hama, killing an estimated 20,000 to 40,000 people.

- Cult of personality: Hafez promoted an image of himself as the eternal leader," ensuring loyalty through fear and propaganda.

In foreign affairs, Hafez adopted an anti-Israel stance, supported Palestinian factions, and intervened in Lebanon's civil war (1975-1990), establishing Syrian dominance in Lebanon until 2005.

Hafez al-Assad ruled Syria until his death in 2000. His son, Bashar al-Assad, an ophthalmologist with no prior military experience, was unexpectedly chosen as his successor.

2. Bashar al-Assad's Rule and the Road to Civil War (2000-2011)

Initial Reforms and the *Damascus Spring"

Bashar al-Assad initially presented himself as a reformer, promising to modernize Syria and allow some degree of political openness. This period, known as the Damascus Spring, saw brief political debates and discussions on democracy. However, by 2001, Assad quickly reversed these reforms, jailing opposition activists and reasserting authoritarian rule.

Economically, he attempted to liberalize Syria's economy, but this mainly benefited the elite and Assad's inner circle, worsening income inequality. Corruption and mismanagement further deepened public discontent.

Political and Social Unrest

By the late 2000s, Syria faced increasing domestic problems:

- High unemployment rates, especially among the youth.

- Droughts (2006-2010), which devastated agriculture and led to rural migration to cities.

- Rising corruption and economic inequality.

These factors set the stage for widespread frustration, making Syria vulnerable to the Arab Spring revolutions that erupted in 2011.

3. The Syrian Civil War (2011-Present)

The Arab Spring and the Uprising Against Assad Inspired by the Arab Spring movements in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya, peaceful protests began in Syria in March 2011, demanding political reforms and an end to corruption. The protests started in Daraa, where security forces arrested and tortured teenagers for anti-regime graffiti. The government's violent crackdown on demonstrators led to mass protests across the country.

By mid-2011, the situation escalated:

- The military responded with extreme force, using live ammunition on protesters.

- Armed rebel groups (such as the Free Syrian Army) emerged, leading to full-scale conflict.

- Foreign interventions increased, turning Syria into a battleground for regional and global powers.

The Fragmentation of Syria and Foreign Involvement

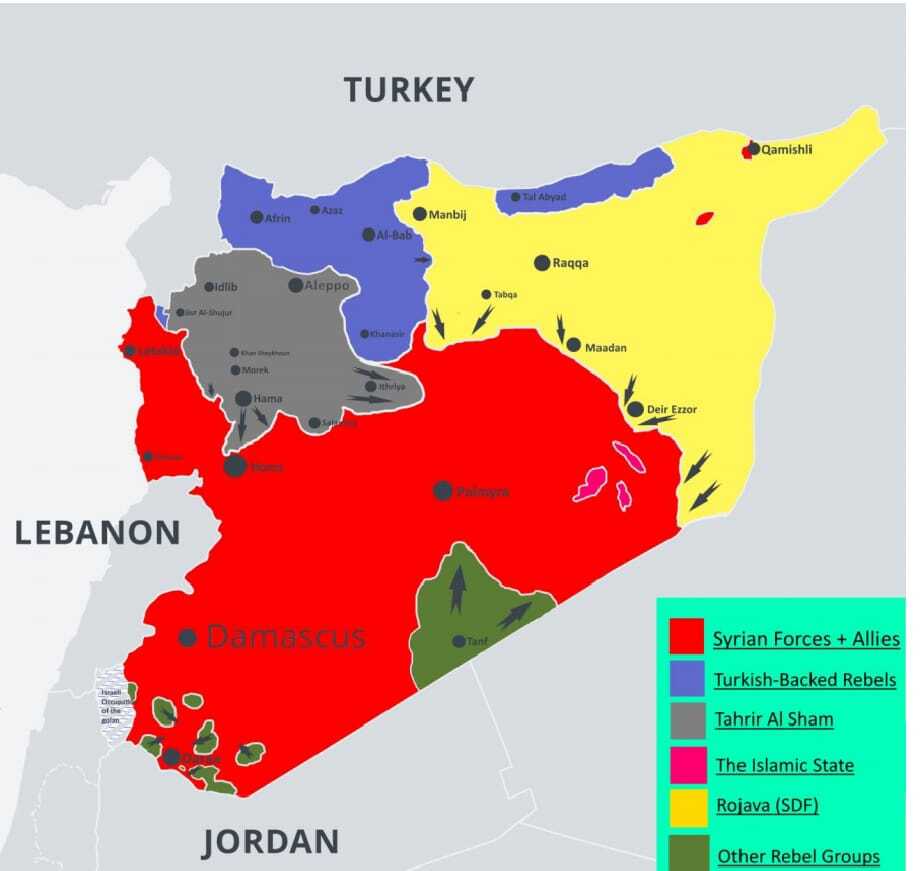

As the conflict worsened, Syria became divided among various factions:

1. The Assad Regime: Supported by Russia, Iran, and Hezbollah.

2. The Syrian Opposition: Backed by the U.S., Turkey, and Gulf states.

3. Kurdish Militias (YPG/SDF): Seeking autonomy in northern Syria.

4. ISIS and Other Jihadist Groups: Exploiting the chaos to establish control.

Russia's military intervention in 2015 saved Assad from collapse, allowing his forces to reclaim key cities like Aleppo and Homs.

Factors That Could Lead to the Fall of Assad: A Detailed Analysis with Case Studies

The Assad regime, despite enduring over a decade of war, remains fragile. Several factors-ranging from economic collapse to internal dissent and foreign intervention-pose significant threats to its long-term survival. Historical case studies of fallen regimes, both in the Middle East and beyond, illustrate how similar factors have led to the downfall of authoritarian rulers. This section explores these factors in depth, providing historical precedents to highlight how they could contribute to Bashar al-Assad's eventual fall.

1. Economic Collapse: The Achilles' Heel of Dictatorships

Syria's economy has been in freefall since the start of the civil war in 2011. Years of war, corruption, sanctions, and poor governance have devastated infrastructure, industries, and trade. The country faces hyperinflation, widespread poverty, and severe food and fuel shortages. Economic desperation has already led to protests in government-controlled areas, signaling growing public dissatisfaction.

Case Study: The Fall of the Soviet Union (1991)

The Soviet Union, like Syria today, was a heavily centralized authoritarian state with a state-controlled economy. Decades of military spending, economic stagnation, and the inability to compete with the West led to widespread poverty. The collapse of the economy eroded public trust the government, ultimately leading to protests, defections within the ruling party, and the disintegration of the Soviet state.

Comparison to Syria

- Similar to the USSR, Syria's economic policies are heavily dependent on foreign aid (especially from Russia and Iran).

- Western sanctions have further crippled Syria's ability to recover.

- The economic hardship is fueling domestic unrest, as seen in protests in Suwayda (2023) where citizens demanded reforms and the removal of Assad.

If Syria's economic crisis deepens, even Assad's strongest supporters may turn against him, just as Communist Party members abandoned Soviet leadership.

2. Political Isolation and the Consequences of War Crimes

Since the start of the Syrian civil war, Assad has been accused of numerous human rights violations, including chemical weapons attacks, mass killings, and torture. While international sanctions have weakened Syria, his status as a war criminal has prevented him from normalizing relations with most countries.

Case Study: Slobodan Milosevic and Yugoslavia (2000)

Slobodan Milosevic, the Serbian leader during the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s, was accused of war crimes and ethnic cleansing. Though he clung to power for years, economic collapse and international pressure led to mass protests and his eventual overthrow in 2000. He was later arrested and sent to The Hague for trial.

Comparison to Syria

Like Milosevic, Assad faces war crime allegations and is isolated from the international community.

Any attempt to normalize relations with Arab nations or Europe is met with resistance due to his criminal record.

If economic pressure increases, even his allies (such as Russia or Iran) may abandon him to protect their own interests.

Should international isolation persist, Assad could face an internal coup or international intervention similar to what happened with Milosevic.

3. Internal Dissent and Protest Movements

While Assad has relied on fear and military control to maintain power, internal dissent is growing, even in government-controlled areas. Economic hardships, corruption, and war fatigue have sparked protests in regions that were once strongholds of the regime.

Case Study: Hosni Mubarak and the Egyptian Revolution (2011)

Hosni Mubarak ruled Egypt for nearly 30 years, maintaining power through a brutal police state. However, economic problems, youth unemployment, and demands for democracy led to the Arab Spring protests in 2011. After weeks of mass demonstrations in Tahrir Square, Mubarak's own military refused to suppress the protests, leading to his resignation.

Comparison to Syria

Like Egypt before 2011, Syria is experiencing growing public discontent.

Protests in Suwayda, Daraa, and Damascus show that frustration is not limited to opposition areas.

The key question: Will the Syrian military and intelligence agencies remain loyal?

If widespread protests emerge and the security forces refuse to back Assad, his regime could collapse just as Mubarak's did.

4. Foreign Pressures and Military Threats

Syria has become a battleground for foreign interests, with multiple actors-including Russia, Iran, the U.S., Turkey, and Israel-playing a role in the conflict. While Assad has relied on Russian and Iranian military support, these alliances are not guaranteed to last forever.

Case Study: The Fall of Saddam Hussein (2003)

Saddam Hussein ruled Iraq for over two decades, maintaining power through an extensive security apparatus. However, after years of war with Iran, economic sanctions, and military interventions, his regime was eventually overthrown in 2003 following the U.S.-led invasion. His allies abandoned him, and he was captured and executed.

Comparison to Syria

- Assad, like Saddam, is heavily reliant on foreign support.

- Russia and Iran prop up his regime, but if their priorities change, they may abandon him.

- Israel continues to strike Iranian military positions in Syria, weakening Assad's security.

If Russia withdraws support due to its economic struggles (partly due to the Ukraine war) or Iran shifts its focus elsewhere, Assad's regime could face a power vacuum similar to Iraq's in 2003.

5. Military Defections and Leadership Struggles

Assad's ability to stay in power has largely depended on the loyalty of the Syrian military and intelligence services. However., history shows that once cracks appear in a regime's security forces, collapse can be rapid.

Case Study: Muammar Gaddafi and Libya (2011)

Gaddafi ruled Libya for over 40 years with an iron fist, controlling the country through a powerful military and intelligence network. However, when the Libyan army started defecting during the 2011 uprising, his power crumbled. NATO's intervention further weakened him, and eventually, he was captured and killed by rebels.

Comparison to Syria

- Assad faces internal tensions within his military, with many commanders frustrated by corruption and war fatigue.

- If key figures in the military defect-similar to Libya in 2011-the regime's collapse could happen quickly.

- Syria's Alawite elite, who dominate the military, may seek a power transition to protect themselves.

If Syria's military fractures, Assad could meet a fate similar to Gaddafi's.

Current Factors Behind the Potential Fall of the Assad Regime: A Detailed Analysis

The Bashar al-Assad regime, once seemingly unshakable, faces increasing pressures that could lead to its eventual downfall. Despite surviving over a decade of civil war, Assad's grip on power is weakening due to a combination of economic collapse, internal dissent, geo political shifts, military challenges, and declining support from allies. While Assad has relied on external backers such as Russia and Iran, the growing instability within Syria and shifting global dynamics suggest that his regime is more fragile than ever. As political analyst Aron Lund notes, "Assad may have survived the war, but he is losing the peace."

1. Economic Collapse: The Regime's Achilles Heel

The biggest threat to Assad's rule today is Syria's worsening economic crisis, which has pushed millions into extreme poverty. The war-torn economy has suffered from:

- Severe inflation (the Syrian pound has lost over 90% of its value since 2011)

- Food shortages and skyrocketing prices

- Sanctions by the U.S. and EU, restricting foreign investment

- Massive corruption and mismanagement

Syria's economic collapse has led to widespread protests, even in previously pro-Assad regions. In August 2023, demonstrations erupted in Suwayda and Daraa due to unbearable living conditions, with protesters chanting anti-regime slogans.

Case Study: Economic Collapse and Protests in Suwayda (2023-2024)

Suwayda, a Druze-majority region that had largely stayed neutral during the civil war, saw unprecedented protests in 2023-2024. Frustrated by economic hardships and lack of services, thousands took to the streets, demanding Assad's resignation. This uprising signals a shift in public sentiment, proving that economic failure can erode even Assad's core support base.

"People can tolerate dictatorship, but they cannot survive without bread, " said an activist from Suwayda in an interview with Middle East Eye.

2. Internal Dissent and Fracturing of the Regime's Support Base

For years, Assad maintained power through an alliance of Ba'athist elites, business oligarchs ,and military commanders. However, recent disputes within the inner circle suggest growing cracks:

Business tycoons vs. Assad: The economic crisis has caused tension between Assad and Syrian businessmen, particularly after he confiscated assets from his cousin, Rami Makhlouf, once Syria's richest man.

Discontent among loyalist communities: Pro-Assad Alawite strongholds (like Latakia and Tartus) are increasingly frustrated by rising poverty and conscription policies.

Corruption and nepotism: High-level corruption has worsened economic misery,turning even some Ba'ath Party loyalists against the regime.

Case Study: The Rami Makhlouf Affair (2020-Present)

Makhlouf, Assad's cousin and financial backer, was stripped of his assets in 2020 after a fallout with the regime. His downfall exposed deep divisions within the ruling elite, signaling that Assad's own circle is not immune to power struggles. Many saw this as a warning that Assad could turn against his allies if they became too powerful."

The moment the economic elite becomes a liability, Assad sacrifices them to maintain his grip on power, " says Syria expert Elizabeth Tsurkov.

3. Russian Disengagement and Waning International Support

Russia has been Assad's strongest military and political backer, providing crucial support during the war. However, after Russia's invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Moscow has shifted its focus and resources, reducing its involvement in Syria.

Key signs of Russian disengagement:

- Reduction in military operations: Fewer Russian airstrikes against rebel-held areas.

- Less economic investment: Russian companies, once active in Syria, are now diverting resources to Ukraine.

- Diplomatic shifts: Russia has been pressuring Assad to reconcile with Turkey and Gulf countries, suggesting that even Moscow sees Syria as an economic burden.

Case Study: Russia's Focus on Ukraine (2022-Present)

Since the war in Ukraine began, Russia has redirected its military and financial resources. Syrian pro-Assad forces have been weakened without Russian airpower. Meanwhile, Turkey has become more aggressive in northern Syria, exploiting Russia's distraction.

A former Russian diplomat told Al Jazeera, "Syria is no longer Putin 's priority. Assad is on his own now.

Without Russian backing, Assad faces a greater risk of military and political isolation.

4. Iranian Influence and the Rise of Hezbollah Militias

While Iran has been Assad's most consistent ally, Tehran's growing influence is also a double-edged sword. Many in Syria, including some within the military, resent the dominance of Iranian-backed militias like Hezbollah and the Fatemiyoun Brigade.

Iran's expansion has led to:

- Tensions between Assad's army and Iranian proxies

- Growing hostility from Israel, which frequently bombs Iranian bases in Syria

- Concerns among Sunni communities about Iran's sectarian policies

Case Study: Israeli Strikes on Iranian Bases (2023-2024)

In early 2024, Israel launched a series of airstrikes targeting Iranian facilities near Damascus and Aleppo. These attacks have intensified, signaling that Iran's presence in Syria is a growing liability for Assad. If Assad becomes too dependent on Tehran, he risks losing the remaining nationalist factions in his military.

"Assad is increasingly seen as an Iranian puppet, which weakens his legitimacy among Syrians," argues Syria analyst Lina Khatib.

5. The Re-Emergence of Rebel and Kurdish Forces

Although Assad reclaimed most of Syria, opposition groups and Kurdish forces still control vast territories:

- HTS (Hayat Tahrir al-Sham) dominates Idlib.

- Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), backed by the U.S., hold north eastern Syria.

- Arab tribes in Deir Ezzor have started revolting against Assad's control.

As the regime weakens, these groups are reasserting themselves, making Assad's grip on power more unstable

Case Study: Arab Tribal Uprising in Deir Ezzor (2023-2024)

In late 2023, Arab tribes in Deir Ezzor launched an armed rebellion against Assad's forces, frustrated by Iran's growing control and economic neglect. The tribes formed alliances with Kurdish forces, posing a direct challenge to Damascus.

One tribal leader told BBC, "We do not want Assad 's rule or Iranian occupation. Syria belongs to its people, not to foreign militias. "

This tribal uprising is a warning sign that Assad is losing authority in key regions, even those once considered 'safe."

Proxies of Global Powers in Syria: The Struggle for Influence

The Syrian Civil War, which began in 2011, quickly transformed from a domestic uprising into a complex international proxy war. Syria's strategic location in the Middle East, its sectarian divisions, and its role in regional power struggles made it a battleground for global and regional powers. The involvement of the United States, Russia, Iran, Turkey, and Gulf states has prolonged the conflict, as each power supports different factions to secure its interests. This proxy war mirrors past conflicts, such as the Cold War-era interventions in Afghanistan, Vietnam, and Angola, where foreign powers used local forces to wage wars on their behalf without direct confrontation. The Syrian case, however, is unique in its intensity and the diversity of actors involved, making it one of the most significant modern examples of geopolitical warfare.

1. Why Syria Became a Proxy Battle field?

Syria's transformation into a proxy battleground did not happen overnight. Several geopolitical, sectarian, and strategic factors contributed to foreign intervention in the conflict.

a) Geopolitical Significance and Strategic Location

Syria is geographically positioned at the crossroads of the Middle East, sharing borders with Turkey, Iraq, Jordan, Israel, and Lebanon. It serves as a crucial corridor between the Mediterranean and the Arabian Peninsula. This makes it strategically important for global powers seeking influence in the region. Russia, for instance, has military bases in Tartus and Latakia, which allow it to project power into the Mediterranean, while Iran sees Syria as a key component of its "Shia Crescent" strategy.

Historically, major powers have sought to control strategic regions to secure military and economic benefits. A parallel can be drawn with the Great Game of the 19th century, where Britain and Russia vied for dominance in Central Asia. Similarly, in Syria, foreign powers have used proxy forces to assert their dominance and deny their rivals an advantage.

b) Sectarian Divisions and the Sunni-Shia Rivalry

The Syrian conflict is deeply rooted in sectarian divides. The Alawite-dominated Assad regime (a Shia offshoot) has historically ruled over a majority Sunni population, leading to internal resentment. This sectarian divide attracted regional powers, particularly Iran and Saudi Arabia, which have long been engaged in a broader Sunni-Shia rivalry.

Iran, a Shia-majority country, supports Assad as part of its regional strategy to maintain influence through allied Shia groups, such as Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Houthis in Yemen. In contrast, Saudi Arabia and other Sunni-majority states, including Qatar, Turkey, and the UAE, have backed rebel factions in Syria to weaken Iranian influence. This sectarian proxy war resembles the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988), where regional powers engaged in a prolonged struggle for dominance through direct and indirect means.

c) The Global Superpower Struggle (Russia vs. the United States)

Beyond regional rivalries, Syria has become a battleground for U.S.-Russian geopolitical competition. The United States initially supported the opposition to topple Assad, whom they viewed as an authoritarian ruler allied with U.S. adversaries (Russia and Iran). Meanwhile, Russia intervened militarily in 2015 to prevent regime change and protect its strategic interests.

This situation is reminiscent of the Cold War conflicts, such as the Vietnam War, where the U.S. backed the South Vietnamese government while the Soviet Union and China supported the communist North Vietnamese. Just as Vietnam became a theater for superpower competition, Syria has become a modern-day stage for power projection, with devastating consequences for the civilian population.

2. The Role of Global Powers and Their Proxies in Syria

A) Russia: The Guardian of the Assad Regime

Russia's primary objective in Syria is to preserve Assad's rule and maintain its military presence in the Mediterranean. The Tartus naval base is Russia's only warm-water port outside its borders, making Syria strategically indispensable. Additionally, Russia views Assad as are liable ally in countering U.S. influence in the region.

How Russia Intervened ?

- 2015 military intervention: Russia launched a large-scale air campaign targeting rebel-held areas, significantly turning the tide of the war in favor of Assad.

- Wagner Group mercenaries: Russia deployed private military contractors (PMCs) to fight alongside Syrian government forces.

- Weapons and diplomatic cover: Russia has provided Assad with advanced weaponry, including fighter jets and missile defense systems while vetoing multiple U.N. resolutions against Syria.

Case Study: Soviet Involvement in Afghanistan (1979-1989)

Russia's intervention in Syria echoes the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, where the USSR supported a communist government against U.S.-backed Mujahedeen fighters. In both cases, Moscow intervened to protect a loyal regime, but faced prolonged conflict due to foreign-backed insurgents.

B) Iran: The Backbone of the Assad Regime

Iran sees Syria as a vital buffer zone against Western and Israeli influence. Losing Syria would break the Shia Crescent a network of Iran-friendly governments and militias extending from Tehran to Lebanon.

How Iran Intervened ?

- IRGC (Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps) commanders were sent to oversee Syrian military operations.

- Shia militias from Iraq, Lebanon (Hezbollah), Afghanistan, and Pakistan were deployed.

- Financial and logistical support ensured the regime's economic survival.

Case Study: Iran's Support for Hezbollah in Lebanon

Iran has used similar proxy strategies in Lebanon, where Hezbollah functions as an extension of Iran's military power. Just as Hezbollah serves Iran's interests in Lebanon, Iran-backed militias in Syria secure Tehran's regional dominance.

C) The United States: The Anti-ISIS and Anti-Assad Strategy

The U.S. initially sought to remove Assad and weaken Iranian and Russian influence. However, after the rise of ISIS, Washington shifted focus to counter terrorism.

How the U.S. Intervened ?

- Funded and trained Syrian rebel groups under the CIA-led Timber Sycamore program.

- Armed and supported Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in the fight against ISIS.

- Launched airstrikes against Assad's military in response to chemical attacks.

Case Study: U.S. Support for Mujahedeen in Afghanistan

The U.S. armed Afghan insurgents against the Soviet-backed Afghan government. Similarly, in Syria, the U.S. supported rebels to undermine Russian influence.

D) Turkey: The Anti-Kurdish Agenda

Turkey's primary concern in Syria is the Kurdish presence along its southern border. The YPG (Kurdish militia), a key U.S. ally, is viewed by Turkey as an extension of the PKK (Kurdistan Workers' Party), which Turkey considers a terrorist organization.

How Turkey Intervened ?

- Military invasions in 2016, 2018, and 2019 targeted Kurdish areas.

- Armed and funded Sunni rebel groups to weaken Kurdish and Assad forces.

Case Study: Turkey's Military Interventions in Cyprus (1974)

Turkey's invasion of Cyprus to protect Turkish Cypriots mirrors its operations in Syria to prevent Kurdish autonomy.

The Future of Syria After the Fall of the Assad Regime: A Holistic Analysis

The fall of the Bashar al-Assad regime marks the end of an era defined by authoritarian rule, internal conflict, and foreign intervention. While this development represents a significant shift in Syria's political landscape, it also opens the door to a range of uncertainties. The absence of a strong central authority creates a power vacuum that various factions, both domestic and international, will seek to fill. The Syrian people, having endured over a decade of war, now face the enormous challenge of nation-building, economic recovery, and political reconciliation. This transition will be shaped by multiple factors, including the establishment of a new government, security concerns, economic reconstruction, and the role of international powers.

As historian Timothy Snyder once stated, "The fall of a dictator is not the end of a struggle; it is the beginning of a new and often chaotic chapter." The post-Assad period will not be an immediate success story, but rather a complex and prolonged process of restructuring Syria's political, social, and economic systems. Whether Syria moves toward stability and democracy or falls deeper into instability and factional conflict depends on how these challenges are addressed.

1. The Political Future: Power Struggles and the Search for Governance

The immediate challenge following Assad's departure is the establishment of a new political order. Unlike other post-conflict states, Syria does not have a unified opposition or a structured transitional framework in place. Over the years, opposition groups have been divided along ideological, ethnic, and regional lines, making it difficult to form a single governing body that represents all Syrians. The absence of a strong political consensus could lead to power struggles between competing factions, including former regime loyalists, opposition leaders, Kurdish groups, and Islamist elements.

One possible outcome is the formation of a transitional government under the supervision of international actors such as the United Nations, the Arab League, or Western powers. This government would be tasked with drafting a new constitution, organizing free and fair elections, and ensuring representation of all ethnic and religious communities. However, the legitimacy of such a government will depend on its ability to gain the support of both the Syrian people and key regional powers. If disagreements arise, the political transition could be delayed or even derailed, leading to further instability.

A more concerning possibility is political fragmentation, where different factions claim control over separate regions. If various militias, tribal leaders, and former opposition forces fail to unite under a central authority, Syria could descend into a new phase of civil conflict, resembling the situation in Libya after the fall of Muammar Gaddafi. In Libya's case, the overthrow of the regime led to warring factions vying for control, foreign interference, and a prolonged period of instability. If Syria follows the same trajectory, the post-Assad period could be marked by chaos rather than progress.

2. Security Concerns: The Threat of Extremism and Regional Conflicts

With Assad's departure, Syria's security landscape will undergo a dramatic transformation. For years, the regime maintained control through its military forces, intelligence agencies, and alliances with foreign militias. Now, in the absence of a strong central authority, multiple security challenges will arise, including the resurgence of extremist groups, sectarian violence, and ongoing regional conflicts.

One of the most pressing concerns is the re-emergence of jihadist groups such as ISIS and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). Although these organizations were significantly weakened over the past decade, they could exploit the power vacuum to regroup and expand their influence. A fragmented Syria would provide them with ideal conditions to recruit fighters, establish strongholds, and launch terrorist operations, both within Syria and beyond. This risk is similar to what happened in Iraq after the fall of Saddam Hussein, where the absence of a strong government allowed ISIS to gain control of large territories, leading to years of instability and violence.

Another major security concern is sectarian and ethnic tensions. The Assad regime was largely supported by the Alawite minority, while opposition forces were primarily drawn from Sunni Arab communities. Now that the regime has fallen, there are fears of reprisals against Alawites and other minority groups, which could spark a new cycle of violence. If these tensions are not addressed through reconciliation efforts and inclusive governance, Syria may face a prolonged period of internal conflict, similar to what happened in Lebanon during its civil war.

Furthermore, foreign military presence remains a significant issue. Countries such as Russia, Iran, Turkey, and the United States have invested heavily in Syria over the years, each supporting different factions. Even with Assad gone, these powers are unlikely to withdraw immediately, as they will seek to protect their interests and secure influence in the post-war settlement. The presence of multiple foreign forces could complicate Syria's transition to stability and turn the country into a prolonged battlefield for competing global powers.

3. Economic Reconstruction: Rebuilding a War-Torn Nation

Syria's economy is in a state of collapse, with much of its infrastructure destroyed, industries non-functional, and millions of people displaced. The post-Assad period will require a massive reconstruction effort, but this will not be easy due to limited financial resources, ongoing instability, and the need for international support. One of the biggest challenges will be rebuilding Syria's devastated cities. Urban centers such as Aleppo, Homs, and Raqqa have suffered extensive damage, with roads, hospitals, schools, and businesses in ruins. The reconstruction process will require billions of dollars in investment, and Syria's ability to access international financial aid will depend on whether a stable and internationally recognized government is established.

Another critical issue is the return of Syrian refugees. Over 5 million Syrians have sought refuge in neighboring countries such as Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan, while millions more are internally displaced. Encouraging their return will require not only political stability but also job opportunities, housing, and basic services. If the economy remains weak, many refugees may be reluctant to return, prolonging the humanitarian crisis.

Sanctions imposed by Western countries on Syria during Assad's rule may also remain in place until a new government proves its commitment to democratic reforms and human rights. Without access to international trade and financial markets, economic recovery will be slow, potentially leading to widespread poverty and unrest.

A useful comparison can be drawn with post-war Germany, which, despite being devastated by World War II, managed to rebuild its economy through the Marshall Plan–a large-scale financial aid program led by the United States. Syria, too, will require a similar international effort to recover from the destruction of war.

4. The Role of International Powers: A New Geopolitical Chessboard

Syria's strategic location in the Middle East ensures that its future will continue to be shaped by global and regional powers. The country has long been a battleground for international rivalries, and even with Assad gone, foreign influence will remain a major factor in shaping Syria's future.

Key international players include:

- Russia and Iran – Having supported Assad for years, these countries will seek to retain their influence in post-war Syria through political and military means.

- Turkey - Ankara will focus on preventing the formation of an independent Kurdish state and securing its southern border.

- The United States and the EU - Likely to push for a democratic transition and economic recovery, but may hesitate to engage fully unless stability is assured.

- Gulf Countries (Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar)-These nations may invest in Syria's reconstruction efforts, but only if the new government aligns with their regional interests.

If foreign powers fail to cooperate, Syria could remain divided and unstable for years. However, if regional and global players agree on a shared vision for Syria, there is hope for a peaceful transition and long-term stability.

A Difficult but Necessary Transition

The fall of the Assad regime is not the end of Syria's challenges but the beginning of a long and complex journey. The future will be determined by how well Syria's political factions manage the transition, whether security threats are contained, and how quickly the economy can be rebuilt. If Syria's leaders and the international community work together, the country has a chance to move toward peace, democracy, and prosperity. However, if divisions persist, Syria could face years of instability and continued suffering.